The Democratic Republic of Congo’s post-colonial struggles are deeply rooted in the violent legacy of Belgian rule and the ruthless exploitation of its vast natural resources. In June 1960, Congo gained independence under the leadership of Patrice Lumumba, its first Prime Minister, but the promise of a sovereign nation quickly dissolved amidst Cold War power plays and internal strife. This is the story of how a hopeful beginning spiraled into a brutal betrayal, leaving a nation vulnerable to decades of instability.

The Brutal Legacy of Belgian Rule

During the late 19th-century “Scramble for Africa,” Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. Unlike traditional colonialism, Leopold treated Congo as his own private possession, unleashing horrific violence to maximize profit from rubber extraction. The Force Publique, a mercenary army, enforced quotas through mutilation – cutting off hands and feet to terrorize the population into submission. It’s estimated that up to 10 million Congolese people died under Leopold’s reign.

Though international outrage eventually forced Belgium to take over administration in the early 20th century, exploitation continued. Until independence, Belgian companies extracted valuable minerals like copper, diamonds, and gold from Congo, accumulating wealth while leaving the Congolese people impoverished. Congo today holds an estimated $25 trillion in untapped mineral reserves—a figure that has historically made it a target for external powers.

Lumumba’s Vision and the Road to Independence

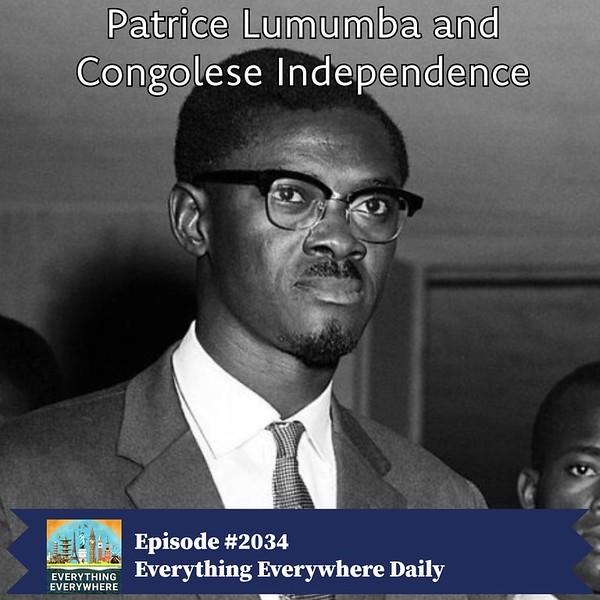

As decolonization swept across Africa in the 1950s, Congolese nationalist movements demanded greater freedom. At the forefront was Patrice Lumumba, a postal clerk who rose to lead the Congolese Nationalist Movement. Like Nelson Mandela or Kwame Nkrumah, Lumumba championed independence, but his vision for a truly sovereign Congo threatened colonial interests.

Independence arrived abruptly in 1960, part of the “Year of Africa” where 16 nations gained freedom. However, the transition was chaotic. Decades of oppression left Congo with a severe leadership deficit—with fewer than 20 college graduates in a population of fifteen million. Despite these odds, Lumumba’s government faced an immediate crisis: Belgium refused to fully withdraw, maintaining control over the military and key infrastructure.

The Collapse of Independence

Just six days after independence, Congolese forces mutinied against Belgian officers. The situation escalated quickly as separatists, backed by Belgian interests, declared the mineral-rich Katanga region independent on July 11, 1960. Katanga held uranium reserves critical to the United States’ Manhattan Project, making it a prime target for outside influence.

Lumumba appealed to the United Nations for military assistance, turning the conflict into a Cold War proxy battle. The U.S. saw Lumumba as leaning towards communism, despite his actual goal being Congolese control over its own resources. He famously stated, “The wealth of Congo should benefit the Congolese, not the profiteers in Brussels, Paris, or New York.”

Betrayal and Assassination

Lumumba’s request for Soviet assistance sealed his fate. While Soviet aid was limited, it confirmed Western suspicions, isolating him on the world stage. By September 1960, the Congolese government collapsed, paving the way for a military coup led by Joseph-Desire Mobutu, later known as Mobutu Sese Seko. Mobutu, backed by Western powers, installed himself as dictator, running a corrupt regime that plundered Congo for decades.

Lumumba was arrested in December 1960 and brutally tortured before being executed by a firing squad in January 1961. His body was exhumed twice and dissolved in sulfuric acid to prevent him from becoming a martyr. One Belgian officer even kept Lumumba’s gold tooth as a souvenir.

A Legacy of Loss

Patrice Lumumba’s story is a stark example of post-colonial betrayal. His death not only deprived Congo of its visionary leader but also set the stage for decades of instability, corruption, and foreign interference. The fight for genuine independence continues to this day, haunted by the brutal reality that Congo’s fate was never truly its own.